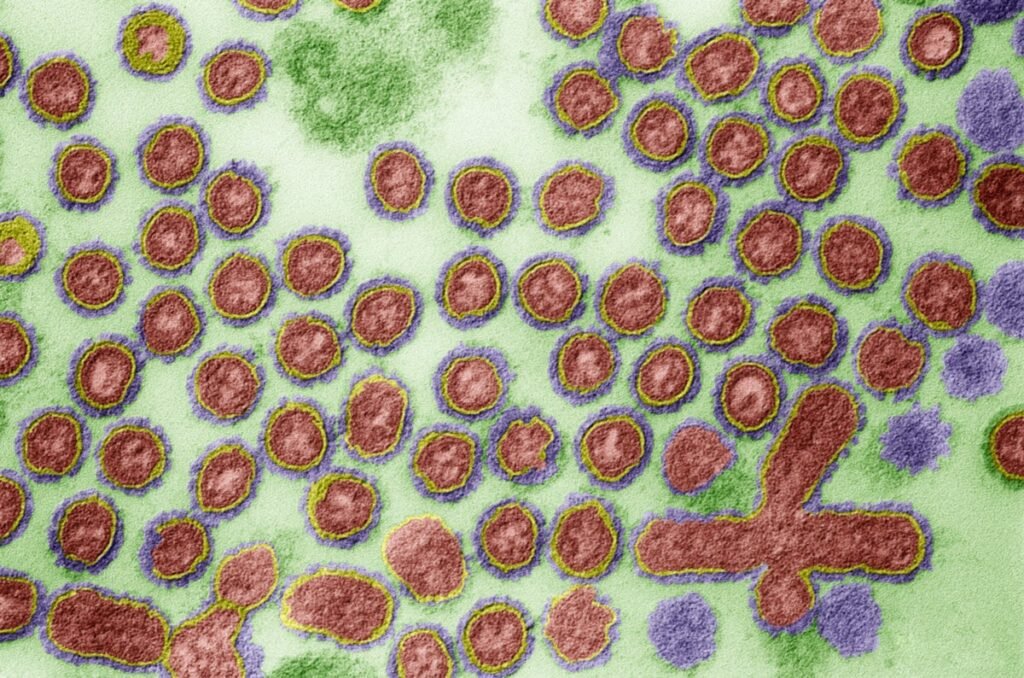

H5N1 avian influenza is circulating. It is moving from animals to humans in a way that has never been seen before. It is spreading to new species and new locations, and this spread is happening largely unnoticed.

So far, 34 cases have been reported in six U.S. states: California, Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, Texas, and Washington. These are just the cases known to health authorities. Not all states test people or animals. Tests for the virus are flawed and in short supply.

Most health officials say they are not too worried at this point because H5N1 influenza is very rare in humans compared to the number of cattle and birds affected. Even if infected, it usually causes very mild symptoms and there is currently no evidence that it can be spread from person to person. That’s a scary scenario. A new virus can cause severe illness in people and can be easily transmitted from person to person. we are not there yet.

About supporting science journalism

If you enjoyed this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By subscribing, you help ensure future generations of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape the world today.

Additionally, the U.S. government is stockpiling H5N1 vaccines. But if this virus does what influenza viruses sometimes do and turns into a pandemic, don’t expect a vaccine to save us. It won’t force humans to mutate slowly, giving people the opportunity to quickly ramp up vaccines.

“It’s going to happen quickly,” said Ali Khan, dean of the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s School of Public Health and an expert on numerous disease outbreaks, from influenza to Ebola.

The world witnessed exactly this happen. The novel coronavirus appeared suddenly and spread across the world before any alarm bells were sounded. Even with the new and rapid technology of mRNA vaccines, it took only about a year after SARS-CoV-2 began its global spread for the first vaccine to be administered into arms. By that point, 300,000 people had died in the United States, and hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions more died around the world before a vaccine was fully deployed.

Even though this particular influenza virus has long scared doctors, scientists, and public health experts, we somehow learned this valuable lesson for early preparation for an avian influenza pandemic. have not learned. H5N1 is a well-known and well-characterized virus, and in theory there could be a large number of vaccines available in case it acquires the ability to easily spread from person to person. there is.

But that’s not it. The United States currently has fewer than 5 million vaccines that are compatible with the H5N1 strain, which is prevalent in cattle and occasionally infects humans. The federal government has a contract to stockpile 10 million pre-filled syringes, but not until spring 2025. It also requires two shots for protection, so there is enough to fully vaccinate just 5 million people. That’s less than 2 percent of the U.S. population, let alone the rest of the world.

And, perhaps hard to believe after our experience with the coronavirus, the United States does not have an approved mRNA vaccine for influenza (one that can be quickly adapted to match mutant strains). Instead, most vaccines stocked to protect against pandemic influenza strains are made using egg-based technology that is nearly a century old. This is an uncertain and time-consuming method that can take months to ramp up in an emergency. “Based on current capacity, we believe we will be able to administer 100 million doses within five months,” said Robert Johnson, director of the medical preparedness program at the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Strategic Preparedness and Response.

These are approved and licensed vaccines. New vaccines must be tested and clear regulatory hurdles. There is currently no official plan for the distribution or administration of an H5N1 pandemic vaccine, but that may change if human-to-human transmission occurs or the virus becomes more virulent.

Vaccine maker Moderna, which launched one of the first coronavirus vaccines using new lightweight mRNA technology, said it is developing an H5 influenza virus vaccine in Phase 2 trials. We have an agreement with the US government. Pfizer, another mRNA vaccine maker, said it is also developing an H5 pandemic influenza vaccine but has not yet reached an agreement with the U.S. government.

Scott Hensley, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is working on developing an mRNA vaccine to prevent influenza, with the hope that it will be produced quickly and be more adaptable to new pandemic strains. There is. But he and his colleagues had to stop that work to deal with the coronavirus and are only just getting back on track.

“If there was a pandemic tomorrow, I have no doubt that we would be introducing not only mRNA vaccines but also traditional egg-based vaccines. So let’s hope we don’t have a pandemic tomorrow,” Hensley said.

The problem with influenza vaccine production begins with the influenza virus itself. It mutates very easily and, even worse, mixes with other viruses. This is why flu vaccines usually change from season to season, and why flu vaccines cannot completely prevent infection.

The H5N1 virus that currently infects cattle first appeared in poultry between 1997 and the early 2000s, and has spread to Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, and is estimated to have killed up to 50% of those infected. is different.

So it makes no sense to produce 600 million doses of H5N1 vaccine in case the virus currently infecting cattle starts infecting and killing humans. It may change again, or it may disappear. “Even if this H5 does cause a pandemic, it likely won’t be the same one that’s circulating in cows[currently],” Hensley said. They will have to adapt to infecting people.

So government agencies, influenza vaccine makers and researchers are closely monitoring the virus, noting any changes and betting on whether they can quickly produce a suitable vaccine. “Viruses are constantly evolving, so it makes no sense to have a continuous stockpile of vaccines, or in large quantities,” Johnson said at an Oct. 8 meeting of the Bipartisan Committee on Biological Defense, a U.S. think tank. It’s impossible.”

There is a theoretical solution to this problem. It’s a flu vaccine that protects against all influenza strains and helps the body’s immune system identify parts of the virus that are consistent from season to season and strain to strain. “We need a moonshot project for a universal influenza vaccine,” Kahn said.

A universal vaccine would protect people not only from seasonal influenza, but also from new pandemic strains, such as the H1N1 strain, which originated in pigs in Mexico in 2009 and has joined the ranks of annual influenza viruses. Dew.

Hensley’s team is developing something close to an mRNA vaccine that provides immunity against all 20 known influenza subtypes. But he said for the first time that this would not be a one-size-fits-all flu vaccine, but rather a primer to give people an initial level of protection. “It’s not a replacement for seasonal vaccination. This problem of producing booster vaccines is still stuck,” he says, because his lab’s vaccines only target known subtypes. Nevertheless, this type of vaccine could potentially address stockpiling issues. Continuous production is less wasteful than one-off operations.

Despite decades of research, no lab has been able to develop a vaccine that protects people from seasonal variations in influenza subtypes. And there was little to no political push for it.

This is in no small part the result of growing hostility among the people. When the coronavirus outbreak occurred, people were largely open to vaccines. Then-President Donald Trump touted the government’s vaccine rollout, but then went on to fuel vaccine skepticism. Neither President Trump nor his Democratic presidential nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris, have mentioned pandemic preparedness in their respective campaign platforms.

Even routine childhood vaccination rates are declining. “Lack of trust in vaccines has put us in a very bad situation. We know that people are dying because they haven’t been vaccinated against COVID-19,” Khan said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that only 11 percent of adults and 7 percent of pregnant women have received the latest coronavirus vaccine.

Some states have loosened vaccine requirements and recommendations, worrying Khan and other public health experts. Vaccines won’t help anyone unless people take them. Politicians who do not emphasize the need to prepare for a pandemic are gambling that the next pandemic will not occur during their term in office. “All of this could come back to roost in the next pandemic,” Khan said.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author are not necessarily those of Scientific American.