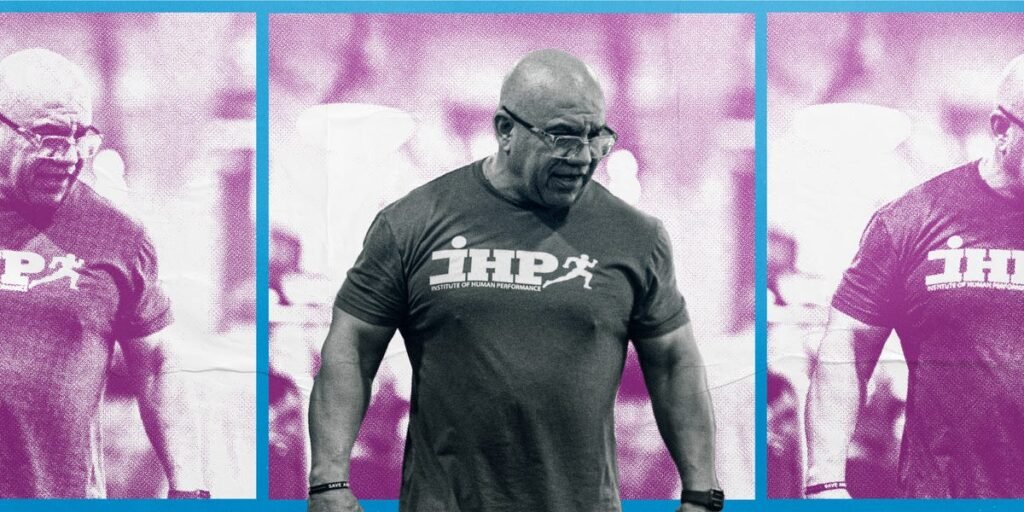

Juan Carlos Santana is a multifaceted person.

The 65-year-old has done it all. He has played almost every sport and tried out “every little league available” as a child. He forms a band that records an album and tours, opens a bar, and works on a Ph.D. He has published several books, including 2015’s Functional Training, and conducted several research studies. He also runs a gym and coaches professional athletes like Manny Ramirez.

The diversity of his experience has created a unique perspective on his work, training and management methods. He is both analytical and creative, thinking outside the box and innovating while implementing rigorous processes to get things done. It’s a tactic that made him one of the founders of functional fitness as owner of the Institute of Human Performance (IHP), a historic gym facility in Boca Raton, Florida.

He has used the gym as an outpost to establish himself as a pioneer in new research and a prolific educator. Men’s Health spoke with Santana about his unusual path to a career in the training industry and the keys to success as a fitness professional.

Men’s Health: How did you get into fitness?

Juan Carlos Santana: Since I was four or five years old, my heroes have always been Tarzan, Hercules, and Samson. These are real men, not Aquaman or Superman-type characters with supernatural powers. They were real people with great physique and extraordinary physical ability. By the time I was six and seven years old, I was already into things like boxing and wrestling. I came to the United States from Cuba when I was almost 8 years old and experienced every little league available. I played almost every sport.

I originally liked the human body, so I went to university to study medicine, but eventually I went to engineering. But it was biomedical engineering. I didn’t want to leave anatomy behind. Then, three semesters short of earning my engineering degree, I quit college, started a band, and toured for four years. It’s a very dark and dirty business. So I thought, “Okay, let’s get into a cleaner business.” We opened a bar. Boca Raton’s first sports bar.

Drinking up profits is not a good business plan, so we went bankrupt after two and a half years. During that critical period, my son, Rio, was born. And I thought, “Hey, I need to go back to school. Live a real life, if not for myself, then for this kid.”

I asked myself the most important question I’ve ever asked myself. “What was I doing when I was happiest?” It was always fitness. It was always a sport. It was always anatomy, movement and training. So I enrolled in exercise science here at Florida Atlantic University and earned my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. It didn’t take long because I had already gotten a few credits from going to school the first time.

After my education, (I) worked as a personal trainer (at a local gym). About a year and a half after I joined there, I thought, “I could do better.” So I built and opened Boca Raton’s oldest gym, the Institute of Human Performance, in 2001. I knew this wasn’t a gym. I probably published seven or eight scientific papers from here. Research happens here, data collection happens here, analysis happens here. Athletes like UFC fighter Manny Ramirez have trained here. We operate a back pain rehabilitation program and also have a wide range of youth programs. It’s more than a gym. People call it church. There’s a culture.

MH: You have called IHP the “mecca of functional training.” How did you arrive at that methodology?

JCS: I came into the field in the mid-90s and was one of the few guys promoting functional training along with Gary Gray, Vern Gambetta, Michael Clarke, and Paul Cech. When functional training came along, it required an esoteric type of approach, a lot of outside-the-box thinking. Can bodybuilding techniques be applied to functional training? There are ways, but you need analytical and artistic traits or qualities to be able to see them. There’s something between the sport and traditional lifting. Once I got that, that’s when I boomed.

MH: You’ve been involved in all areas of the fitness industry, including training, research, and business ownership. Have you ever noticed that in many/most of the rooms you’ve been in throughout your career, you’re the only person who looks like you?

JCS: When I’m in the room, I don’t even do a racial inventory. Yes, I recognize it when a Hispanic person is doing something, when a black person is doing something, when a white person is doing something. But I don’t equate[someone’s success]with race or ethnicity.

I take stock of my thought process. There aren’t many people like me, for better or for worse. I’m not saying I’m special or anything like that. There aren’t many people who are analytical, artistic, and have strong moral values like I try to live my life.

Minorities, on a human level, do not lack the ability to live properly and therefore to inspire and motivate others. If you have come from difficult times, I understand that. That means it needs a little more polishing.

Mauricio Pais

MH: What is the key to overcoming that hardship and succeeding in the fitness industry?

JCS: It’s about (nurturing) culture. (At IHP) everyone is on the same page. Believe me, we have different genders, different identities, and different religions. I also look at my own staff. But we all get along.

(As a leader) you have to embody that culture. If you don’t show up, you can’t maintain a culture where people show up. How can we expect people to work hard or follow good morals if we ourselves do not do so? How are you going to encourage others to do so? It must be done through the example of leaders. If a leader is true to themselves and understands that they don’t want to join or lead the culture, that’s fine. But hire someone to do it for you.

It also has a real live feel. Live by your principles. I just strive to be the best version of myself and I hope that inspires people and motivates people. If you do that, you’ll be fine.

Here at IHP, we have a principle of “picking up pieces of paper.” When you’re in the bathroom, you often leave small pieces of paper on the floor when you pull out a tissue. And most people don’t pick it up. (Most people) will walk on it. It’s a decision you choose and one you have to make. But since no one is looking at it (or even if they don’t pick it up), they think it’s okay. No one knows. It doesn’t matter.

That piece of paper is not a piece of paper. That piece of paper is your life. When you walk on that piece of paper, you have failed to do the right thing by even the slightest bit. It’s all about the little things. Do the right thing when no one is looking.

Cori Ritchey, NASM-CPT, is the Health & Fitness Associate Editor at Men’s Health and a certified personal trainer and group fitness instructor. You can see more of her work at HealthCentral, Livestrong, Self, and more.