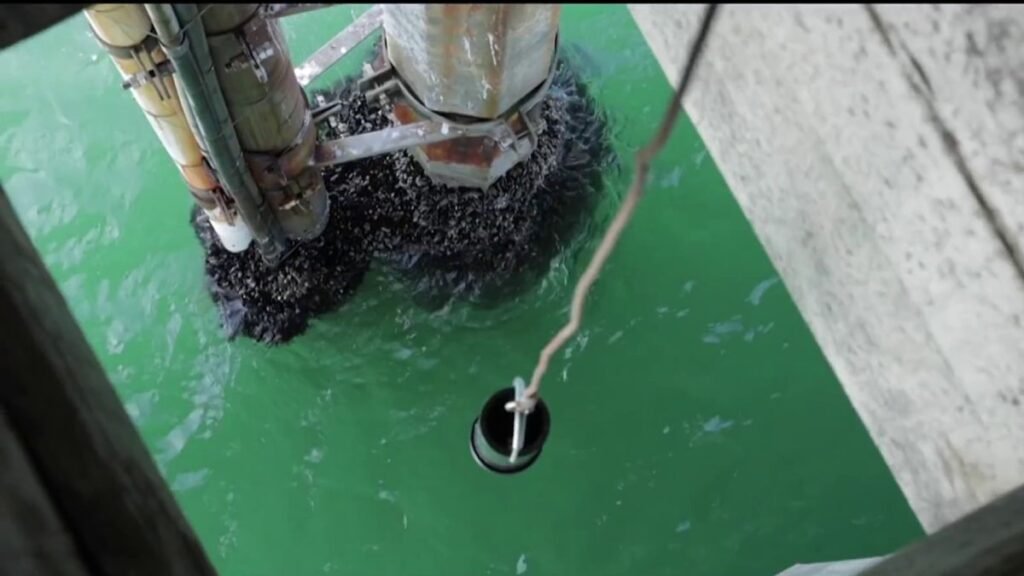

At the end of the nearly 1,100-foot-long Scripps Pier in La Jolla lies a small room that holds a lot of history. Every day, scientists lower a small container into the ocean through a hole in the chamber to collect samples. They’re looking for two simple measurements.

“We manually take samples from the ocean and measure temperature and salinity,” said Melissa Carter of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

What makes this simple task remarkable is that it has been done in the same location every day since 1916, and scientists today are using the same techniques as they were a century ago. The data collected is the longest continuous record of such measurements in the Pacific Ocean, meaning it is one of the best places to track long-term changes occurring in the Pacific Ocean. I will.

“This is kind of a gold mine for basic ocean data sets like this,” Carter said. “We’re doing it the same way they’ve done it in the past, so we can understand those trends over time.”

What they’re looking at is long-term changes in ocean temperature and chemistry. A graph of 108 years of data shows that temperatures have risen markedly since around the 1980s, with nearly all of the warmest water years occurring in the past 10 years.

“So we’ve seen the oceans warming, almost 3 degrees Fahrenheit over 100 years,” Carter said.

There are many reasons why a few degrees of warming is important. First, as the ocean warms, it expands. This can cause sea levels to rise, pushing water higher up the coastline and causing erosion.

Second, warmer oceans provide more energy to tropical cyclones, helping them grow stronger and faster. Hurricane Milton reached the Gulf of Mexico in record warmth and strengthened at the fastest rate on record. And it came as Hurricane Helen, now one of the deadliest storms in U.S. history, hit.

Third, scientists say ocean warming could cause more El Niño winters, which could change weather patterns around the world. This winter’s El Niño brought record rainfall to parts of California, including the historic Jan. 22 storm that dumped nearly 3 inches of rain in three hours on San Diego. This is about a quarter of what the city normally receives in a year.

“El Niño used to be said to occur every five to seven years, but now it’s happening every three to five years, so there’s a change happening,” Carter said.

These simple daily measurements help put the pieces of the puzzle together.

“In an El Niño year, we may see even more salt water coming in,” Carter said. “So knowing temperature, salinity and nutrients is very helpful in putting that signal together.”

Scripps Pier is one of 10 locations along the California coast where these daily measurements are taken. It’s called the Coastal Station Project. And while some stations have been measuring for more than a century, others for just a few decades, they all show the same trend of rising water temperatures.

“We need this station, as well as many other datasets, to really put together a complete picture of what’s happening along our coast,” Carter said.

As a side note, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography recently installed a live underwater camera on a pier in the same area where daily measurements are taken. You can find it here.