We use data from the third wave of the Casa Monitor Smaragd Survey. The Smaragd Survey is an online survey conducted by infas36042 with an online-representative sample of 10,000 participants in Germany. The data are representative of the federal state. We received data from infas360 on March 17th, 2022. infas360 assigns randomized identifiers, making it impossible to identify individual participants. The survey was conducted between January 3rd and January 31st, 2022, and respondents voluntarily participated. Infas360 has a pool of pre-registered target persons (Casa Monitor) who representatively reflect the German online population aged 18 years and over. Infas360 assigned participants to the survey until 10,000 individuals completed it (opt-in non-probability sampling). To ensure representativeness, infas360 uses blended calibration, which integrates non-probability samples with probability-based surveys to reduce sampling error in population estimates. Despite these efforts, some sampling error may remain, potentially biasing our subsequent inference.

To become part of the online panel, potential participants must give written consent to the data privacy policy (see https://mingle.respondi.de/privacy-policy. The participants are informed about the use for scientific research, anonymization is through this data privacy policy. Since participants get individual links they cannot participate several times. The participants were informed that the survey did not trigger powerful emotions or physical pain. Hence, the Economic Ethics Committee of the University Alliance Ruhr and RWI approved our research (certificate No. 2024_1_SS). We confirm that all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Participants were not informed of the topic of the survey prior to participation. Exact response rates are not available for our specific survey, but the Casa Monitor typically has a response rate between 30 and 40%. Participation is incentivized with €0.25 per 5 min. Participants in the third wave received an average of €0.50, so the average duration was about 10 min.

The questionnaire of the survey can be found in the FDZ Data Description43. It was possible to choose not to answer any question and continue with the questionnaire. As (child) vaccinations were a controversial topic at the time, there could be a selection bias in terms of who participated in the survey. In the Appendix, we compare the descriptive statistics of the respondents to administrative information and show that they are very similar in terms of demographics and regional coverage (see Table A1). Hence, we do not observe a strong selection, at least in terms of observables. The survey sampled individuals but not households. This means that we learn about the vaccination intentions of one parent but not of the other. Yet, the decision to vaccinate children is likely to be made jointly by both parents. While actual vaccination status is asked for adolescents, we believe that this is not an issue here. Yet, vaccination willingness is asked for children under 12. The own opinion of one parent, then, does not necessarily reflect the eventual vaccination behavior of the household.

Sample selection

A total of 10,000 individuals aged between 18 and 90 years participated in the survey. We restrict the sample to parents who are, at most, 60 years old and have children younger than 18 years. While we observe whether respondents have children, we do not know the exact age of the children (only whether they are below 12 or 12–17). We exclude individuals who reported not to vaccinate their children because they were too young, thereby assuming that their children were below five years old. However, it is unclear whether some parents may not have sufficient knowledge of vaccination regulations, despite media coverage being prevalent on the topic. Parents with children under age 12, who report their children as too young, have a median age of 34 years, compared with 38 years for those who do not. This suggests that the parents were well informed. All in all, 1,819 parents are included in the final sample. 1,051 of them have children below 12 years of age, whereas 1,145 had children aged 12–17 (we do not exclude parents who have children in both age groups).

Unfortunately, our sample does not include information on how many children the respondents have within the two categories 5–11 and 12–17. Possibly, parents have two children aged 5–11 and have one child vaccinated but not the other. According to our auxiliary analysis with data from the German Microcensus of the year 2020 that covers around 400.000 individuals, among all households with children between 5 and 17, 70.7% have either exactly one child between 5 and 11 (29.4%), one child between 12 and 17 (29.2%) or one child 5–11 and one child 12–17 (12.1%). The remaining 29.3% have at least two children in one of the two age groups.

Outcome

The survey questions on vaccination (directed to the parents) read as follows:

Have you been vaccinated against the Corona virus? Possible answers: Yes or No.

Have you vaccinated your children (between 12 and 17)? Possible answers: Yes or No.

Would you like to have your children under 12 vaccinated? Possible answers: Yes (as soon as possible), not yet decided, no.

While vaccination for adults and 12–17 year was already possible in January 2022, it was not yet universally available for all children below 12. While vaccinations were approved for this age group in Germany in November 2021, not every child had received an actual offer at a local vaccination center in January 2022. Thus, the third question is hypothetical, while the first two questions are about actual vaccination status.

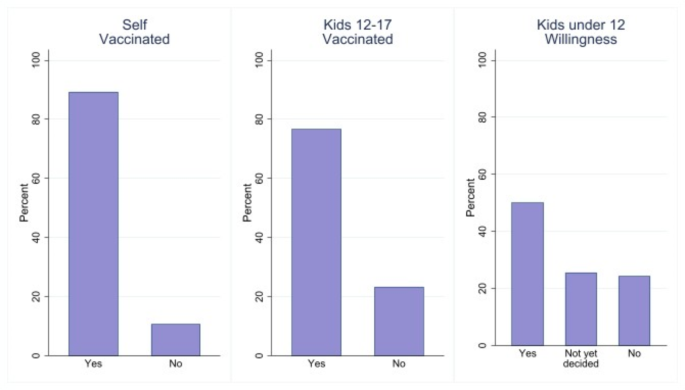

Fig. 1

Distribution of vaccination willingness. Smaragd Survey, Wave 3, January 2022. The left panel only includes parents with children below 18 (n = 1,819). The middle panel only includes parents with children between 12 and 17 (n = 1,145). The right panel only includes parents with children under 12 (n = 1,051).

The responses are shown in Fig. 1. Approximately 90% of parents in the sample are vaccinated at least once. This finding is consistent with the average vaccination rate in Germany. Moreover, 75% of children aged 12–17 are vaccinated. This is in contrast to the stated willingness to vaccinate children between 5 and 11 years of age, once a vaccine is available (which is the case as of today but has not been so for everybody in January 2022). In our sample, 50% are planning to vaccinate their children, while one-fourth has not decided yet and another fourth plans not to vaccinate. Interestingly, a willingness of 50% is still significantly higher than the official vaccination prevalence, which was around 20% in July 2024. We use this stated willingness as an important dependent variable, keeping in mind that this differs from actual vaccination behavior. As long as the difference between stated and actual preferences does not systematically vary by socioeconomic status, we do not consider this a fundamental problem44.

Institutional setting

On January 27, 2020, Germany reported its first case of the new coronavirus. From March, the German government implemented measures to control the spread of the virus, including recommending the cancellation of events with more than 1,000 participants and imposing travel restrictions. On March 13, all state governments decided to close schools from March 16 to April 19, 2020. A minimum distance of 1.5 m was imposed in public places and people were only allowed to be in public places with one other person from outside their household. Restaurants and many service businesses were closed. Restrictions were gradually lifted under strict hygiene and distance rules, and primary schools in North-Rhine Westphalia (NRW), the largest federal state – to name one example – reopened on 4 May. Pupils returned to normal schooling on a rotating basis before the summer holidays.

As infections increased, a “lockdown light” was introduced in November 2020, with restaurants, bars and gyms closed and private gatherings limited to 10 people. The lockdown was tightened further, and primary schools in NRW were again closed from mid-December to the end of February 2021, along with most shops and service businesses. In March 2021, a gradual easing of the lockdown began, depending on local infection rates. From 23 April to 30 June 2021, the Federal Emergency Brake was in effect, imposing uniform measures based on local incidence rates, including curfews and alternative day schooling for high incidence areas.

Adjustments to testing and infection control measures were agreed on 10 August 2021. Access to many public places required proof of vaccination, recovery or a negative test (the so-called “3G rule”). Free public testing ended on October 11, but was reintroduced on November 13. Large events were allowed with hygiene plans.

On November 19, 2021, new infection control measures were approved, including a home office mandate where possible and a 3G rule in workplaces otherwise. Mandatory testing was introduced for staff and visitors to retirement homes, nursing homes and healthcare facilities. The 3G regulation also applied to local and long-distance transport and domestic flights. States could continue measures such as mandatory masks and contact restrictions, but could no longer impose nationwide exit restrictions, travel bans or school and business closures. Stricter measures were linked to hospitalization rates, with the introduction of 2G (vaccinated or recovered) and 2G-plus (vaccinated or recovered plus testing) rules depending on the severity of hospitalization rates.

Corona mitigation measures increasingly pressured unvaccinated people by requiring regular testing. Vaccination in Germany began on December 27, 2020, but initially vaccines were scarce, and priority was given to the elderly and those in high-risk occupations. On June 7, 2021, this prioritization was lifted, but demand still outstripped vaccine supply. In June, the STIKO (Standing Committee on Vaccination) recommended vaccination for children aged 12–17 only if they had pre-existing conditions (such as adiposity or immunodeficiency) or were in close contact with a high-risk person. The vaccine could be given to children without pre-existing conditions if they wanted it and their parents accepted the risks. Two months later, STIKO recommended the vaccine for all children aged 12 to 17. For younger children, ages 5 to 11, STIKO waited until early January 2022 to recommend the vaccine, again only for those with pre-existing conditions or in close contact with a high-risk person. As before, vaccination was possible without a pre-existing condition if parents accepted the risks.

The vaccination campaign against COVID-19 received broad support across most political parties. Until the end of 2021, the government was formed by the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD), who actively promoted vaccinations as a critical tool in combating the pandemic. The opposition parties, the Greens (Grüne) and the Free Democrats (FDP), also supported the vaccination efforts. Their primary criticism was not of the campaign itself but of its pace, arguing that the government needed to accelerate the rollout to reach more people more quickly. After joining the government with the SPD in December 2021, the Greens and FDP maintained their commitment to the vaccination campaign, emphasizing its importance in ensuring public health.

The Left Party (Die Linke) also supported the vaccination campaign, recognizing its significance in protecting vulnerable populations. However, their support was less vocal compared to the governing parties. Alongside their endorsement of the campaign, they especially highlighted systematic weaknesses in the health sector and demanded higher wages for healthcare personnel, emphasizing the need for broader reforms in the healthcare system. In stark contrast, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) opposed the vaccination campaign. The AfD not only criticized the government’s approach but also spread fears about potential side effects of the vaccines. They claimed that the government was suppressing discussions about these side effects, fostering skepticism and resistance among certain segments of the population.

Potential factors related to vaccine hesitancy

The literature has identified various factors associated with vaccine hesitation and parental intention to vaccinate their children, including socioeconomic status, demographic factors, and concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness45,46,47,48. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the control variables used in the regressions. 45% of the parents in the sample are male, with an average age of 42. 58% work full-time, and the majority has a university-entrance diploma (Abitur). Given the large differences in willingness to vaccinate across the political spectrum49, we also account for party preferences. We include all control variables in our regressions because the computation of variance inflation factors does not indicate problematic multicollinearity (see Table A3 in the Appendix).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics.

A potentially relevant characteristic of child vaccination behavior is its own (parental) negative experience with the coronavirus crisis. Specifically, we test whether parents who had stronger experience with restrictions due to the pandemic (e.g., because of school closures) are more willing to vaccinate themselves and their children. Figure 2 reports the distribution of days when the federal emergency brake (Bundesnotbremse) was put on in the county and when schools were closed. Starting in April 2021, the federal emergency brake became effective when the seven-day incidence in a county exceeded 100 per 100.000 people. It mainly included restrictions in gathering with people from other households, night-time curfews, requirements of a negative Corona test to shop, shutdowns of cultural activities, and regular tests and schooling only every second day. A seven-day incidence of more than 165 in three consecutive days led to school closures in the county.

Theoretically, there could be reverse causality between vaccination rates and the number of days with an active emergency brake, as higher vaccination rates could have successfully reduced the spread of the virus, resulting in fewer days with an active brake. However, we observe correlations that are very close to zero. There may be two reasons for this. First, the emergency brake was effective from April 2021, when vaccines were still scarce. Second, vaccines were ultimately more effective in reducing hospitalisations than in preventing infections.

Fig. 2

Distribution federal emergency brake and closed schools. Own calculation. The figure shows the number of days with an active federal emergency brake or closed schools between April 23 and June 30, 2021, when the federal emergency brake rules were in effect.

Statistical analysis

Depending on the nature of the outcome variables, we use different regression techniques. In our baseline regression, which are the characteristics of vaccination status, we run a linear probability model using OLS. Because of the binary nature of the outcome vaccination status, Logit or Probit regression would also be possible. However, in our application, the marginal effects after Logit and Probit are the same as the coefficients in the linear probability model. Thus, we choose the simplest model. Among those with children under 12, we take two approaches. First, we run the simple linear probability model and exclude parents who answer to be ‘not yet decided’. In addition, we estimate a multinomial logit regression where we include “yes”, “not yet decided” and “no” as separate unordered categories and report its marginal effects. Note here that one regression produces three sets of marginal effects (one per outcome category), with the effect of each variable summing to zero across all three categories and without imposing an order between these categories.

In order to increase the flexibility of the regression models, we also include interactions of relevant variables. We do this in the baseline specifications of Table 2 below. In particular, we want to allow for the possibility that persons with different experiences of Corona restrictions might have different effects of labor market participation and party preferences on vaccination behavior. Thus, in addition to the baseline variables, we also include interactions of days with federal emergency brakes (and days with closed schools) with the indicator of full time work and with all indicators of party preferences. For the sake of legibility and to keep the focus of our analysis, we do not discuss the interaction terms but calculate and report average marginal effects of all baseline variables.

The marginal effects are calculated as follows. Consider, as an example, the effect for fulltime work. Let us denote the outcome variable = Y, Fulltime = X1, Days federal emergency brake = X2, and Days with closed schools = X3. Then, the regression looks like Y = \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\) + \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\) X1 + \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\) X2 + \(\:{\beta\:}_{3}\) X3 + \(\:{\beta\:}_{4}\) X1*X2 + \(\:{\beta\:}_{4}\) X1*X3 + …. The marginal effect of Fulltime for each person is then \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\) + \(\:{\beta\:}_{4}\) X2 + \(\:{\beta\:}_{5}\) X3, where person specific values of X2 and X3 are plugged in. Finally, the average of all individual marginal effects is reported. We used the margins command in Stata to calculate marginal effects and standard errors. Since the results with interactions are very similar to those without (reported in Table A4), we go on with the simpler model without interactions from Table 3 onwards.

Throughout the regression analysis, continuous variables are standardized while binary variables are not. Finally, note that this kind of analysis does not allow for any causal interpretations. Both, the variables on the left hand side and many of those on the right hand side of the regression equation are choice variables which are most likely affected by unobserved variables. Thus, variables like education or voting preferences are endogenous. Nevertheless, it is possible to interpret the results as associations which still allows to draw relevant conclusions.