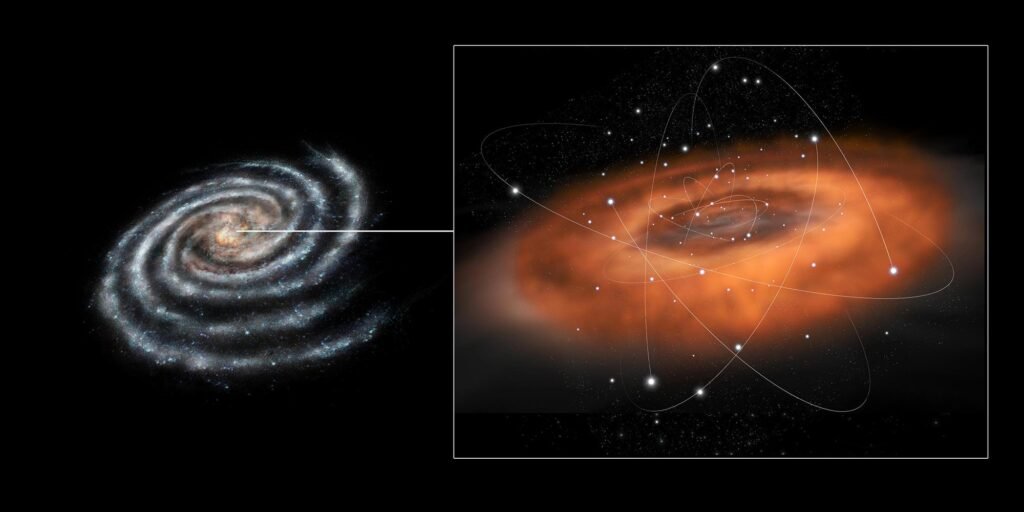

This conceptual diagram shows activity at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, where the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* resides. (ESA/C. Carrow)

Supermassive black holes, optimal oxygen supply, and rising medical costs.

Invisible to casual stargazers is Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy more than 26,000 light-years away, eating up matter around it. Capturing it will require data from a variety of telescopes, including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. Astrophysics doctoral student Scott McKee (SM’23) and collaborators published May 9 in Astrophysical Journal Letters in a study investigating the role of black holes in galaxy formation. The observatory’s archives were used in the published research. By matching 13 X-ray images taken in 2005 and 2008, researchers discovered an “exhaust vent” at the top of a known gas stream chimney hundreds of light-years from the galaxy’s center. ” was identified. The vent system, thought to be a waste disposal site for the scraps spewed out by Sagittarius A, could help researchers identify how often black holes consume and eject cosmic material. be. It may also explain how the mysterious galaxy-sized Fermi and eROSITA bubbles around Sagittarius A* came to be. —RM

Every year, millions of critically ill patients around the world require ventilators to help them breathe. Doctors aim to maintain these patients’ peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) levels, or the amount of oxygen in their blood, between 88 and 100 percent, but specific goals within this range are not important. It was thought that there was no. However, research led by Kevin Buell (SM’24), a pulmonary and critical care researcher at the University of Chicago Medicine, shows that there is an optimal SpO₂ level, which just differs from person to person. In the study, published March 19 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers used a machine learning model trained on randomized trial data to identify patients with severely ill patients on ventilators. Predicted the ideal SpO₂ level for adults. They may be able to determine optimal blood oxygen levels using specific demographic and health data, such as age and heart rate, and for patients whose SpO₂ levels are within the algorithm’s ideal prediction range. found that there would be an overall reduction in mortality of 6.4%. If these discoveries are implemented in clinical practice, they could lead to more personalized care and improved survival rates for critically ill patients. —SM

Since 2000, health care prices have risen faster than any other sector of the U.S. economy. Because most Americans receive health insurance through their or a family member’s job, these increased costs are passed on to employers rather than directly to consumers. So how are employers responding to this increase, and what are the broader economic implications? 20246, led by Harris Public Policy’s Zarek Brot-Goldberg This month’s research report answers these questions using data on hospital mergers that have been found to increase health care costs. Brot-Goldberg et al. compared non-healthcare employers that were more affected by hospital mergers with those that were less affected. As a result, a bleak situation became clear. For every 1 percent increase in health care costs, employers reduced the number of employees by 0.4 percent and salaries by 0.37 percent. This equates to a 2.5 percent increase in unemployment insurance payments. This shows that rising health care costs are having a significant impact not only on employers and workers, but also on federal and state budgets.