Main findings

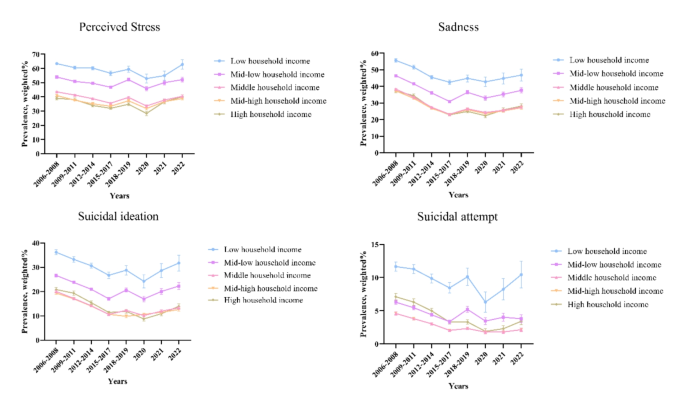

This study is the first long-term follow-up study over 17 years to examine the relationship and trends between household income level and adolescent mental health. Our findings showed that lower household income levels were associated with mental health indicators such as stress, sadness, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts among Korean adolescents. Furthermore, our study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly changed trends in adolescent mental health. In the pre-pandemic era, negative mental health indicators had a decreasing pattern, but during the pandemic they spiked and shifted to an increasing pattern. This highlights the huge impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on young people’s mental health, and goes beyond the physical symptoms they are facing, such as respiratory illnesses. It also emphasizes the need to address mental health challenges. Furthermore, they identified the most significant risk factors for poor mental health as being female, alcohol consumption, and smoking status.

plausible mechanism

We found that students from low-income households tend to experience higher levels of stress, sadness, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts. This may be due to feelings of relative advantage compared to peers and recent societal trends that emphasize wealth28. Adolescents from low-income households may feel isolated from their higher-income peers, which can lead to low self-esteem and psychologically depressing thoughts and behaviors.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating these problems by highlighting and exacerbating existing inequalities. During lockdowns, low-income students are more likely to experience cramped living conditions, limited privacy, and difficulty accessing online education, potentially increasing feelings of stress and isolation. Additionally, low-income households were more likely to experience job loss or reduced work hours during the pandemic, further increasing financial stress and its impact on adolescents’ mental health30.

Furthermore, parental psychological distress, rather than socio-economic status per se, may contribute to these outcomes. Parental care is essential for adolescents’ identity development, and insufficient parental care can lead to psychological instability in children. In collectivist cultures like South Korea, families play an important role in interpersonal relationships, and poor family functioning is closely related to poor children’s mental health32. This phenomenon can lead to adolescents feeling isolated and surrounded by fewer peers33. School factors also play a role, as adolescents’ self-esteem related to school social capital influences mental health similarly to parental factors34. Another potential mechanism is increased academic pressure in low-income households, where adolescents may feel a greater need to succeed academically to improve their future prospects 35 .

Additionally, female gender, alcohol consumption, and smoking status have been established as risk factors for poor mental health in previous studies. This trend is particularly pronounced among young people from low-income settings 36 , 37 , 38 . These adolescents may engage in these risky behaviors as a coping mechanism to cope with the increased stress and psychological strain they face, which further exacerbates their mental health problems39. The interaction between these factors creates a vicious cycle that is difficult to break, highlighting the need for targeted interventions that address both the socio-economic and behavioral aspects of adolescent mental health. I am.

These factors combine to contribute to the negative mental health outcomes observed among adolescents from low-income households.

Comparison with previous research

Several studies have linked household income to adolescent mental health, including studies in Kenya (n = 2,195), Norway (n = 1,354,393), Canada (n = 29,722), and Germany (n = 2,111). 10,40- 42. Although these studies have shown an association between lower household income levels and increased mental illness in adolescents, they are limited by small sample sizes and There were limitations due to the wide range of age groups included. In contrast, our study is characterized by a large population-based design, with a particular focus on the 12- to 18-year-old age group. Additionally, our research spans over 17 years and provides insight into long-term trends and patterns in adolescent mental health. Furthermore, we categorized income into five groups to gain a detailed understanding of the impact of income inequality on the mental health of Korean adolescents. This approach allows governments and societies to implement political interventions and support programs tailored to the specific needs of each income group. By considering both the COVID-19 pandemic and income levels, our study provides a comprehensive understanding of how external factors like the pandemic differentially impact each income group. You can. This highlights the need for a comprehensive understanding when considering the impact of the pandemic on changes in mental health indicators.

Policy implications

Several previous studies have mainly focused on predicting and preventing suicidal behavior in adolescents and identifying associated factors43. However, our study highlights that perceived stress levels and sadness are also important indicators of adolescents’ mental health, as they can lead to suicidal behavior. Adolescents are vulnerable and can be affected by a variety of factors, so it is essential that governments and schools focus on these negative mental health indicators45. In particular, we found that female gender, alcohol, and smoking were significant risk factors for negative mental health indicators. Therefore, we will explore why low-income female students are more prone to mental illness and solutions. Additionally, school- and community-based drug abuse prevention programs, such as alcohol and tobacco, needed to be carefully prepared for at-risk youth46.

Furthermore, many initiatives aimed at improving the mental health of adolescents have reduced the overall incidence of mental health problems in this group47,48. However, with the advent of the pandemic, these mental health problems have increased significantly2,17. This issue requires urgent and serious discussion and resolution. Addressing the mental health of young people is critical and requires both governments and educational institutions to work together to support students suffering from mental health conditions. Early identification of each student’s mental health issues and provision of counseling services is an important step49. Additionally, it is critical to encourage physical activity and face-to-face social interaction among students, away from the digital realm of smartphones and social media50. Additionally, we need to foster the social connections that have been severed during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between household income and adolescent mental health indicators using a Korean database. Furthermore, our study is distinguished by its longitudinal and large-scale population-based approach, encompassing data from multiple countries. This database allowed us to identify trends before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The result is a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between income and mental health, and how these trends have been affected by the pandemic. We also identified several risk factors that further exacerbate the relationship between income and mental health, including female gender, alcohol consumption, and smoking status.

However, our study also has some limitations. First, KYRBS is administered to school students, which introduces bias as it excludes students other than those who are home-educated or those who have dropped out. Second, the data represent subjective responses rather than objective measures, which is an inherent limitation of survey-based cohort studies. Adolescents may not be aware of their household income, which may bias their responses. Furthermore, due to the sensitivity of mental health issues in Korean society, even though the survey was anonymous, participants may feel pressured to provide socially acceptable answers and underreport their symptoms. It is thought that there is a sex. This pressure, combined with a potential reluctance to discuss sensitive topics, can exacerbate nonresponse bias as certain participants may avoid or skip questions they find uncomfortable. There is. Third, the utilized KYRBS dataset does not include a temporal component, which precludes analysis of causal relationships between depression and other variables. Finally, as this study is completely based on existing survey data with predefined questions, it is not possible to investigate the specific reasons and mechanisms by which household income level affects adolescents’ mental health. It’s difficult.

Despite various limitations, this study still has strengths.