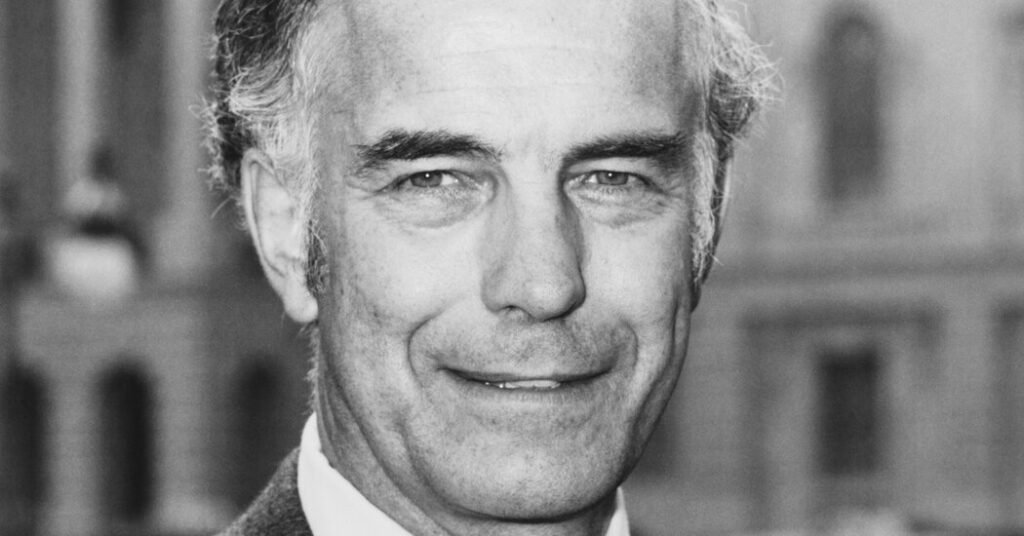

Daniel J. Evans, a moderate Republican who served three terms as governor of Washington state, served as a senator and was repeatedly considered for vice president, died Friday night. He was 98.

His son, Dan Evans Jr., said Evans died of natural causes at his Seattle home, about five blocks from where he grew up.

“Our father lived an extraordinarily fulfilling life,” Evans’ sons, including Mark and Bruce Evans, said in a statement released Saturday. “From serving in public office to working to advance higher education and mentoring those seeking public service, he continued to do so until the end. He touched the lives of so many people,” they said.

Mr. Evans, a descendant of 19th-century Puget Sound shipping sailors, served as Washington state’s 16th governor from 1965 to 1977, championing education, civil rights and environmental causes, and served a somewhat unsuccessful senate term from 1983 to 1989.

He was a climber, skier, sailor and eloquent speaker, and during his first term as governor he emerged as a new face in national politics at a time when the Republican Party was reeling from the crushing defeat of Senator Barry M. Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election.

In 1968, Evans was chosen to deliver the keynote address at the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach when Richard Nixon was nominated for president. Emerging as the Republican Party’s star candidate, Evans eschewed the usual party self-praise and called for America to tackle its problems: the Vietnam War, urban blight, civil rights and unemployment.

Evans, who was frequently mentioned as Nixon’s running mate, was dropped from the running after endorsing Nixon’s progressive rival, New York Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, angering conservatives who had supported California Governor Ronald Reagan.

Mr. Evans resisted being called a moderate Republican, saying in a 2010 speech to the Seattle Rotary Club that he was “tired of hyphenated Republicanism. ‘Moderate,’ ‘Conservative,’ ‘Mainstream’ are all adjectives that divide us. But the term suited Mr. Evans well, and in 1965, his first year as governor, he tried to expel the far-right John Birch Society and its supporters from the state Republican Party.

“False prophets, false philosophers, professional bigots and subversives, leave our party,” he told the Republican State Committee.

He disagreed with many of the central tenets of conservative politics. He supported abortion rights, opposed a constitutional amendment requiring a balanced federal budget, and argued that while “overspending” could lead to disaster, tax increases were sometimes necessary. “Fiscal prudence is not included in George H. W. Bush’s famous line, ‘Read my lips: no new taxes,'” he said.

President Gerald R. Ford twice considered Evans as his running mate: first in 1974 when he succeeded Nixon after his resignation amid the Watergate scandal, and then in 1976 when Ford won the Republican presidential nomination, but he ended up choosing Rockefeller as his running mate in 1974 and Kansas Senator Bob Dole as his running mate when Jimmy Carter was elected president in 1976.

As governor, Evans increased aid to higher education and helped establish the state’s community college system. He also enacted legislation to clean up our air, water and coasts and to protect endangered species. In 1970, Washington became the first state to establish a Department of Environmental Quality.

At a time when urban riots shook the nation, he went to poor areas of Seattle and established a center to provide state services. He used his executive power to establish the Washington State Commission on Indian Affairs in 1967 and the State Council of Women in 1971. In 1969, he appointed the first black members to the boards of trustees of the University of Washington and Seattle Community College. He also supported atomic energy, tax reform, and the abolition of the death penalty.

He allied with Democrats throughout his career. In 2011, former Democratic House Speaker Thomas S. Foley, who represented Washington from 1965 to 1995, said Evans was “one of the most thoughtful and able governors in the country, and his advice was always one that the Democratic-majority House of Representatives listened to and followed. He earned our respect and admiration.”

Evans, who was re-elected in 1968 and 1972, boosted the state’s economy and created jobs at a time when unemployment was soaring. He traveled to the Soviet Union and China to recruit businesses and helped resettle Vietnamese refugees after the Vietnam War.

In 1977, he became president of The Evergreen State College in Olympia, an innovative four-year institution he helped found as governor.

Gov. John Spellman appointed Mr. Evans to fill the vacancy created by the death of Sen. Henry M. Jackson in September 1983. Two months later, Mr. Evans won a special election for a six-year term.

As a senator, Evans introduced bills to protect one million acres of Washington Wilderness and to create the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, and while he generally supported President Reagan’s policies, he became dissatisfied with the Senate and did not seek reelection.

In a 1988 New York Times Magazine article titled “Why I’m Leaving the Senate?”, he said he had looked forward to “dueling debates, an exchange of ideas.” Instead, he found “speeches read to a nearly empty chamber,” “bickering and long periods of paralysis,” and “a Legislature that seemed to have lost its focus and its soul.”

Daniel Jackson Evans was born in Seattle on October 16, 1925, the son of Daniel Lester Evans, a civil engineer, and Irma (Eide) Evans.

He graduated from Seattle’s Roosevelt High School in 1943 and enlisted in the Navy, serving as an ensign on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific shortly after the end of World War II. He became a structural engineer in Seattle after earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in civil engineering from the University of Washington. He served as a lieutenant in the Korean War from 1951 to 1953, serving on a destroyer and serving as an aide at the armistice negotiations at Panmunjom.

In 1959 he married Nancy Ann Bell, who died in January at age 90. In addition to his three sons, he is survived by nine grandchildren.

From 1953 to 1965, Evans worked as an engineer and was a partner in a Seattle company. But he also entered politics. He was elected to the state House of Representatives in 1956, served four terms, and then ran for governor in 1964. Nationally, Democrats dominated the state, with Lyndon B. Johnson defeating Barry Goldwater for president. But Evans defeated two-term Democratic Governor Albert J. Rosellini, winning with 56 percent of the vote. Evans was reelected in 1968 and again in 1972, defeating Rosellini.

In 1972, long before the serial killings came to light, Ted Bundy, a University of Washington graduate, joined Evans’ campaign for a third term. For a time, he followed Evans’ opponent, Rosellini, around the state, recording his speeches and reporting back to Evans. When Bundy’s past was revealed, it caused a bit of a scandal.

After retiring from politics, Evans founded a Seattle-based political consulting firm and served on the boards of numerous business, cultural, civic, and environmental organizations. He served on the University of Washington Board of Trustees from 1993 to 2005, and as chairman of the board from 1996 to 1997. In 1999, the university’s School of Public Policy was named after him.

The school cited his accomplishments in an online statement released Saturday: “He believed deeply in civility, mutual respect and bipartisanship, and throughout his long career in public service, he refused to sacrifice his principles for expediency or personal advancement,” the statement said.

Climbing was a lifelong passion of his: In 1973, while president of Evergreen College, he rappelled down the side of the school’s 122-foot-tall clock tower. Later, in his 80s, he told a college friend he’d had hip replacement surgery so he could go hiking with his grandchildren. That goal was achieved in 2010, when Daniel Jackson III accompanied his father and grandfather on a multi-day hike in the Olympic Mountains.

In 2017, a 1.5 million-acre wilderness area in Olympic National Park was renamed in his honor. A biography, “Daniel J. Evans: The Autobiography,” was published in 2022. “I wish I’d picked a sexier title,” he told Seattle’s KIRO News Radio. “But the title doesn’t matter. It’s what’s inside that matters.”

Hank Sanders contributed reporting.

Adam Clymer, who served as a reporter and editor at The Times from 1977 to 2003, died in 2018.