public health

Public Health Written by Mark Shepherd, September 30, 2024

Harvard University Kennedy School

problem:

Universal access to affordable health insurance has been a long-standing U.S. policy goal and is at the heart of the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or “Obamacare”), one of the greatest social reforms of the 21st century. It was. In the 10 years since it went into effect in 2014, the percentage of Americans without health insurance has declined sharply and is now near an all-time low. However, approximately 26 million people in the United States remain uninsured, a much higher percentage than in the United States, where nearly everyone has universal health insurance. Furthermore, progress in expanding insurance coverage to non-elderly people has largely stalled since 2016. Meanwhile, economists’ understanding of health insurance has advanced significantly, with a decade of new research revealing both its clear benefits as well as its surprising tradeoffs. The difficult task of achieving universal health coverage within the current system in the United States.

The uninsured rate has remained surprisingly stable since 2016, despite significant policy changes and the widespread availability of highly subsidized insurance.

fact:

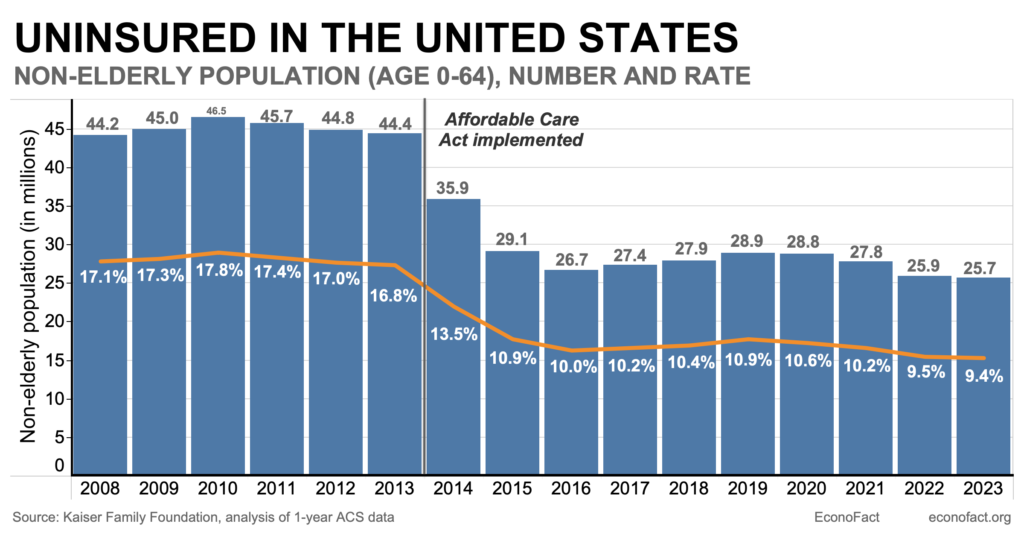

As of 2023, the most recent year for which data is available, a total of more than 26 million people living in the United States lack formal health insurance. Analysts often focus on the uninsured rate for ages 0 to 64, because nearly all (99%) senior Americans age 65 and older typically have insurance through Medicare. The uninsured rate for non-elderly people will be 9.4%, or 25.7 million people, in 2023 (see graph). Uninsured Americans are more likely to be low-income and racial minorities. In 2023, 23.6% of Hispanic adults ages 19 to 64 were uninsured. This is nearly double the rate for black adults (11.1%) and much higher than for non-Hispanic white adults (7.0%) and Asian adults (6.8%). ), according to the latest census figures. Children under 19 have additional coverage options, including access to the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Therefore, although racial and ethnic differences still exist, children tend to have lower uninsured rates than working-age adults. The highest uninsured rate is among non-citizens (32.9%), who are often poor and ineligible for subsidized public programs (Census, Figure 5). According to data from the American Community Survey, the uninsured rate among non-elderly adults varies widely by state, ranging from a low of 3% in Massachusetts to a high of 18.7% in Texas. This variation is due in part to demographic differences in the composition of each state’s population, but also due to some states’ decisions not to expand Medicaid to low-income households as allowed by the Affordable Care Act. There is. In these “non-expansion” states, 32.5 percent of poor households are uninsured, compared to 18.7 percent in expansion states (see Figure 6). The Affordable Care Act (ACA), known as “Obamacare,” aimed to provide access to affordable health insurance for all Americans. The United States does not have universal health care, but rather a patchwork system of private and public health care providers (see here). More than 50% of Americans receive health insurance through employment-based private health insurance. Because not everyone is eligible to receive health insurance through work, the ACA aimed to increase access to health insurance with three strategies. First, it expanded eligibility for Medicaid, the nation’s public health insurance for low-income Americans, to people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Second, it created new subsidies for private insurance to make it more affordable for middle-income groups (100-400% of the poor). Finally, it required citizens to purchase health insurance or pay tax penalties. This was known as the ‘personal obligation’ and was abolished in 2019. After the enactment of Obamacare’s core coverage, the number and percentage of Americans without health insurance declined sharply. Regulations were introduced in 2014 but have since plateaued. In 2013, 44 million non-elderly Americans (16.8%) were uninsured; by 2016, that number had declined by one-third to 26.7 million (10.0%). (see graph). Researchers are studying the extent to which various provisions of the ACA contribute to lowering the proportion of Americans who lack health insurance. A 2012 Supreme Court decision that gave states the option not to expand Medicaid allowed researchers to compare results in states that expanded Medicaid with those that did not. Using this natural experiment, a vast body of research has found strong evidence that Medicaid expansion reduces uninsuredness. Other studies have also found evidence that increased subsidies increase private insurance enrollment and reduce uninsuredness. Finally, there is ample evidence that the tax penalties of the “individual mandate” have increased coverage, but the effect has been more modest than expected. Since 2016, the uninsured rate has remained largely stable despite changes in policy. The uninsured rate rose slightly from 2016 to 2019 as the Trump administration weakened certain ACA provisions. For example, as of 2019, it reduced funding for enrollment assistance and zeroed out the tax on the uninsured. However, an attempt was made in 2017 to “abolish and replace” this system. The ACA itself was defeated by a narrow margin, with the late Sen. John McCain casting a dramatic “no” vote in the middle of the night that decided the outcome. Despite the pandemic and associated economic disruption, the uninsured rate declined from 2020 to 2023, breaking from the usual pattern of increases in uninsured during recessions. The main reason for this is policy changes enacted in response to the pandemic, particularly the expansion of generous insurance subsidies starting in 2021 and the periodic redetermination of Medicaid eligibility that was in place through 2023. It was stopped. There was a change in the source of compensation. . More than 25 million people have left Medicaid since provisions suspending Medicaid redetermination expired in 2023. At the same time, enrollment in the ACA insurance marketplace is also rapidly increasing (21 million people covered as of 2024, nearly double the number of enrollees in 2021). There is strong evidence that expanding health insurance coverage in the United States saves lives and protects people from financial risks. The past decade has seen substantial research that has deepened economists’ understanding of the causal effects of health insurance coverage, particularly for the poor. New research from large randomized experiments and the ACA’s Medicaid expansion finds that expanding health insurance coverage significantly reduces mortality. These results are consistent with those of earlier studies that exploited changes in state policy and the introduction of Medicaid in the 1960s and 1970s. In terms of outcomes other than death, the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment found significant improvements in mental health, but no effects on physical health. There is already ample evidence that insurance protects people from financial risks, and these findings were confirmed by evidence from the Oregon Experiment and the ACA Medicaid expansion. Expanding coverage leads to increased health care utilization and costs. New evidence confirms classic research that purchasing insurance leads to higher overall health care costs, a phenomenon known as “moral hazard.” Consistent with this, the share of GDP spent on health care increased significantly before and after enactment of the ACA (from 16.9% of GDP in 2013 to 17.6% of GDP in 2016). There is growing debate about how much of this additional spending is waste or represents valuable medical care that the uninsured previously could not afford. Most of the remaining uninsured (about 60%, or 15 million people) will be eligible for free or subsidized coverage through the ACA, and about 40% will be eligible for completely free coverage. Very likely. Nevertheless, the main reason cited for being uninsured (by two-thirds of uninsured people) is “unaffordability of coverage.” This suggests that non-price coverage barriers, such as lack of knowledge and the hassle and burden of enrolling in public programs, are key barriers to coverage expansion, as highlighted in several recent research papers. It suggests that.

Despite the significant and rapid expansion of insurance coverage since the enactment of the Affordable Care Act in 2014, approximately 26 million Americans still lack health insurance. The experience of the past decade has shown that achieving universal coverage within complex and voluntary health insurance systems is a difficult challenge. Despite significant policy changes and the wide availability of highly subsidized coverage, the uninsured rate has remained surprisingly stable since 2016. But the stakes are high. Research over the past decade has solidified the evidence that expanding health insurance coverage, even if it comes at a cost, reduces mortality and protects people from financial risks. If policymakers want to further meaningfully expand coverage, evidence suggests that reducing non-price barriers to insurance coverage, such as information provision and enrollment complexity, is essential.

Topic:Medicaid/Public Health

Source link