This story is part of “Latinx in Fitness,” a series of articles showcasing the unique experiences of Latinx trainers, athletes, and gym owners within the fitness community. Read the rest of the stories here.

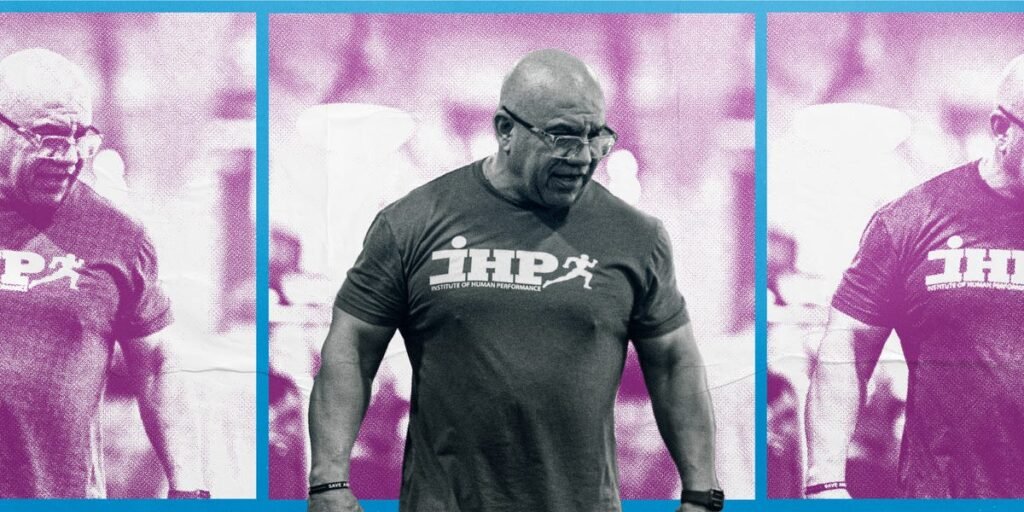

Juan Carlos Santana is a man of many talents.

At 65, he’s done it all. He played “every Little League” as a kid, played just about every sport, formed a band that recorded an album and toured, opened a bar and is currently working on his PhD. He’s published several books, including 2015’s “Functional Training,” and conducted several research studies. He also owns a gym and trains professional athletes like Manny Ramirez.

His diverse experiences have given him a unique mindset in how he works, trains and manages. He is analytical yet creative, innovative and outside-the-box thinking while implementing rigorous processes to get things done. This strategy has made him one of the founders of functional fitness as owner of the historic Institute of Human Performance (IHP) in Boca Raton, Florida.

From his base in the gym, Santana has established himself as a pioneer of new research and a prolific educator. Men’s Health spoke with Santana about his unconventional path to a career in training and his secrets to success as a fitness professional.

Men’s Health: What got you started in fitness?

Juan Carlos Santana: From the age of 4 or 5, my heroes were Tarzan, Hercules, and Samson. Not superhumans like Aquaman or Superman, but real people. They were big, real people with incredible athletic ability. By the age of 6 or 7, I was into boxing, wrestling, and things like that. I came to the US from Cuba when I was 8 and played every little league. I played almost every sport.

I loved the human body, so I went to college to study medicine, but I ended up studying engineering, but in biomedical engineering. I wasn’t going to give up on anatomy. Then I was three semesters away from getting my engineering degree, so I dropped out, started a band, and toured for four years, which is a very dark and dirty job. So I thought, “I’m going to do something cleaner,” and I opened a bar. It was the first sports bar in Boca Raton.

Two and a half years later, I was bankrupt, because swallowing profits is not a good business plan. During that critical period, my son Rio was born, and I thought, “Dude, I gotta go back to school. If not for myself, then I gotta give this kid a real life.”

I asked myself the most important question I’ve ever asked myself: “What was I doing when I was happiest?” It was always fitness. It was always sports. It was always anatomy, movement, training. So I enrolled here at Florida Atlantic University in the Exercise Science department and got my bachelor’s and master’s degrees. It didn’t take long, because I’d already earned some credits when I went to my first school.

After I got my education, I worked as a personal trainer (at a local gym). About a year and a half into working there, I thought, “I can do better.” So in 2001, I founded and opened the Institute of Human Performance. It’s the longest-running gym in Boca Raton. I knew it wasn’t just a gym. We’ve probably had seven or eight scientific papers published here. We’ve had research done here, data collection and analysis. We’ve had guys like Manny Ramirez and UFC fighters train here. We run a back rehab program, we have a great youth program. It’s not just a gym. People call it a church. It’s a culture.

“you If you don’t come, others will come. How do you tell people Work hard and follow through Do you have good morals if you yourself do not do so?

MH: You’ve called IHP the “Mecca of Functional Training,” how did you discover this methodology?

JCS: I got into the field in the mid-90s and was one of the few advocates of functional training along with Gary Gray, Vern Gambetta, Michael Clarke and Paul Cech. When functional training came on the scene, it required a esoteric approach, a lot of outside-the-box thinking. Can you apply bodybuilding techniques to functional training? There is a way, and it takes both analytical ability and artistic character to figure it out. There is something between this sport and traditional lifting. Once I figured that out, I was very successful.

MH: You’ve been involved in all facets of the fitness industry – training, research, running a business – have you ever felt like you were the only person who looked like you in many/most of the places you’ve been in your career?

JCS: When I’m in a room, I don’t even think about race. Sure, when a Hispanic person is doing something, or a black person is doing something, or a white person is doing something, I notice it. But I don’t equate[someone’s success]with race or ethnicity.

I take stock of my thought process. For better or worse, there aren’t many people like me. I’m not saying I’m special or anything like that, but there aren’t many people with the analytical mind, the artistry, or the strong moral compass that I value in life.

Minorities are not lacking, on a human level, the ability to live well, to inspire and motivate others. If they have been through difficult times, that’s understandable. They just have to try a little harder.

Mauricio Paiz

MH: What is the key to overcoming those struggles and succeeding in the fitness industry?

JCS: It’s about cultivating culture. Everyone is on the same page (at IHP). Trust me, we are all different genders, we are all different identities, we are all different religions. I see that even among my own staff. But we all get along.

(As a leader) you have to embody the culture. You can’t have a culture where people show up if you don’t show up. How can you ask people to work hard or follow good morals if you don’t? How can you inspire others to do so? It has to be through the leader’s example. If a leader is true to themselves and recognizes that they don’t want to plug in and lead the culture, that’s fine. But hire people who will.

Live authentically. Live with faith. I just want to be the best version of myself, and I hope that inspires people, I hope that motivates people, and then it works.

At IHP, we have a principle that we follow: pick up the paper. When you take out the tissue in the bathroom, most people leave a little piece of paper on the floor, right? And most people don’t pick it up. They step over it. It’s a decision that you step over. It’s something that has to be done. But you think it’s okay because no one sees. No one knows. It’s inconsequential.

That piece of paper isn’t just a piece of paper. That piece of paper is your life. When you walk on that piece of paper, you are neglecting to do the right thing. Even if it’s the little things. The little things are everything. Do the right thing when no one is watching.

Want to read more first-person perspectives from Latinx fitness pros about overcoming obstacles, breaking barriers, and achieving success? Click the links below to read all the stories:

read more