Horseback riding is a difficult physical activity, but can we change the very structure of our bones? Archaeologists at the University of Colorado Boulder set out to answer this question in a new study. Their findings suggest that the answer is more nuanced than previously thought. The study, published in Science Advances, reveals that horse riding can leave subtle marks on the human skeleton, but it does not conclusively link skeletal changes to horse riding alone.

The team, led by Lauren Hosek, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Boulder, examined a wide range of evidence, from medical research on modern equestrian tribes to thousands of years of human remains. They found that activities such as horseback riding can change the shape of bones, particularly the hip joint, but these changes are not limited to horseback riding. Sitting for long periods of time or doing other repetitive activities can also cause similar changes.

“There are very few cases in archeology where it is possible to clearly link specific activities to skeletal changes,” Hosek explained in a recent statement. The discovery challenges long-held theories about the origins of horseback riding and the role of horses in human history.

The history of equestrianism challenges old theories

There has been much debate about the influence of horseback riding on human history, especially the domestication of horses. One long-standing theory, known as the Kurgan hypothesis, suggests that the Yamnaya people near the Black Sea first rode horses around 3500 BC. According to this theory, the domestication of horses played a vital role in the spread of subsequent languages. It has since evolved into many modern Indo-European languages, including English and French.

William Taylor, co-author of the study and curator of archeology at the University of Boulder Museum of Natural History, noted that the Kurgan hypothesis relies on skeletal evidence from the Yamnaya site. Supporters of this theory point to the wear and tear on the Yamnaya skeletons as evidence that ancient people crossed Eurasia on horseback.

However, new research challenges this view. Horseback riding can leave traces on the human skeleton, but skeletal changes alone cannot conclusively prove that the Yamnaya were equestrians, the study argues. Taylor stressed that more comprehensive evidence, including genetic data and horse remains, is needed to determine when humans first began using horses for transportation.

“A human skeleton alone is not enough evidence,” Hosek said. “We need to combine that data with evidence from genetics, archaeology, and even horse remains.”

Researching the effects of horseback riding

Researchers have found that horseback riding can subtly change the structure of the hip joint. For example, if you bend your leg at the hip for a long time, such as during a long ride, the ball and socket joint of the hip joint can rub, eventually stretching the socket into an oval shape. However, other activities can cause similar skeletal changes, such as sitting for long periods of time or riding in a horse-drawn carriage.

Horsek noted that even 20th-century Catholic nuns who had never ridden horses showed similar hip changes after spending long hours in horse-drawn carriages traveling through the American West. This evidence highlights the complexity of interpreting skeletal changes in archaeology, as other means of transportation, such as ox carts and donkey carts, can cause similar bone changes.

“Over time, repeated intense pressure, such as pushing together in a bent position, can cause skeletal changes,” Hosek says.

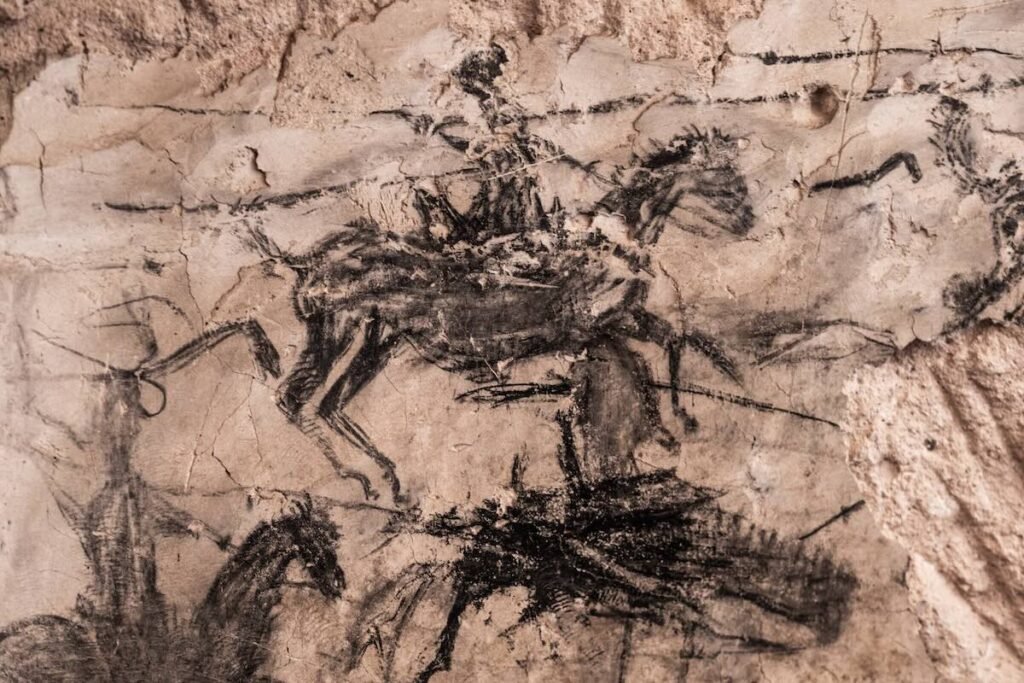

Skeletons recovered from the Yamnaya culture in Volgograd Oblast (Image: XVodolazx/Wikimedia Commons).

Challenge to the past timeline

The earliest incontrovertible evidence that horses were domesticated for transportation was around 4,000 years ago near Russia’s Ural Mountains, where archaeologists have unearthed horses, harnesses, and chariots. . However, the exact time when humans started riding horses remains unclear, and there is some evidence to suggest that they may have been riding horses much earlier in other regions.

Dr. Taylor noted that this study casts doubt on whether the Yamnaya people, who lived around 3500 BC, were the first cavalry people.

“At least at this time, there is no body of evidence to suggest that the Yamnaya kept domestic horses,” he said in a recent statement.

While this discovery complicates our understanding of when horseback riding began, it also highlights the importance of using a multidisciplinary approach to investigating human history. Researchers hope that by combining skeletal analysis with other archaeological and genetic evidence, they will be able to paint a more accurate picture of the relationship between humans and horses.

Taylor says, “Much of our understanding of the world, both ancient and modern, rests on when people first started using horses for transportation.”

For now, the mystery of when humans first sat in a saddle remains an unsolved mystery, but research like this one brings us closer to answering that question.

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is a science communicator at JILA (the world’s leading physics research institute) and science writer for The Debrief. Contact her by following her on X or email her at kenna@thedebrief.org.